European soccer learns a new virtue: patience

Why have so few managers been fired this year? Pandemic economics play a role, but there are bigger forces at work, too.

LONDON — Enrico Preziosi could hardly have held Thiago Motta in higher esteem. As a player, Motta spent only a single season at Genoa, the Italian soccer team Preziosi owns, but he made such an impression that, a decade later, his old boss cited him as his ideal professional. “A smart and empathetic man,” Preziosi said. “He taught me many things.” Not long after that ringing endorsement, the men were reunited. At the end of his playing career, Motta had moved into coaching and was developing a glowing reputation in Paris St.-Germain’s youth system. Genoa, as is its default setting, was struggling. And so in October last year, Preziosi turned to Motta, the “player of his soul,” to arrest the slide.

And then, two months later, he fired him. Motta, that smart and empathetic man, had lasted all of nine games.

It was vintage Preziosi. This, after all, is what he does: He fires coaches. In the 17 years since he bought Genoa — Italy’s oldest club — he has changed his coach 27 times. He quite often churns through three in a single season. He once fired Alberto Malesani twice in the same campaign. He has fired one coach, Ivan Juric, three times. Italian soccer has a word — mangiallenatore — for owners like him: coach eater.

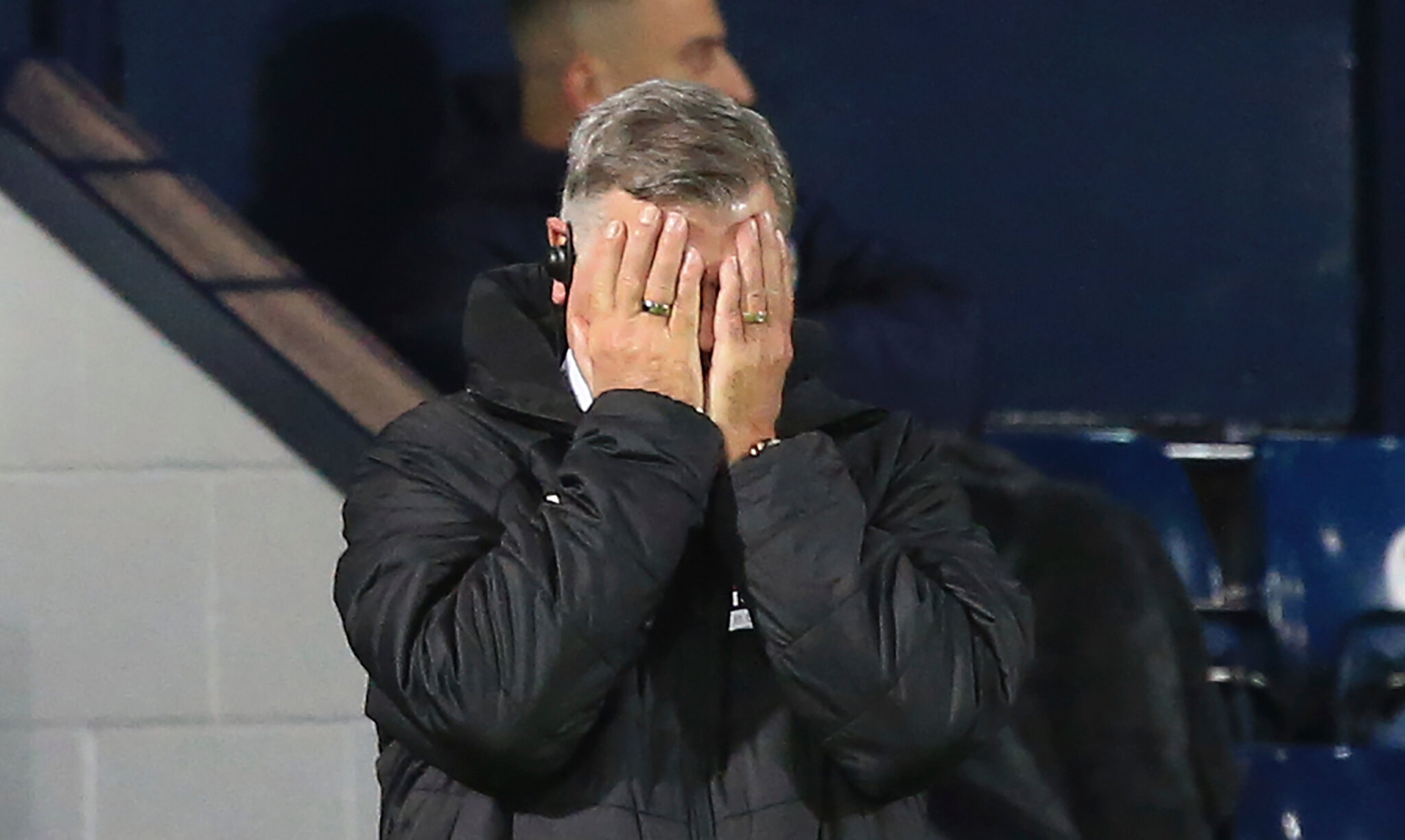

Preziosi fired another manager this week, dispensing with Rolando Maran, whom he had appointed in August but who had not won a match since September. If all of that felt reassuringly familiar, though, the circumstances were unusual. This year, many of Preziosi’s peers in Europe’s top five leagues have discovered a virtue hitherto rarely associated with owners of soccer clubs: patience. More than a third of the way through the season, only one other Serie A team, Fiorentina, has fired its coach. In La Liga, only Celta de Vigo has changed managers. In the Premier League, Sam Allardyce had to wait until last week to be parachuted into West Bromwich Albion. His appointment was only the second time a Premier League team had fired a manager in 2020.

In France and Germany, things are a little more familiar. Four managers — at Metz, Dijon, Nice and Nantes — have been fired in Ligue 1 so far this season. Four have also been dismissed in the Bundesliga, though the continuing implosion of Schalke accounts for two of them. Even there, though, most owners waited as long as they could before deciding on change. David Wagner, the first of the two Schalke coaches to be fired this season, lost his job after failing to win for 18 games; the club had been determined to give him a chance to turn the situation around. And of the eight dismissals in France and Germany this season, half happened this month.

Much of this newfound restraint can, of course, be explained by the coronavirus pandemic. Clubs across Europe are facing immediate shortfalls of hundreds of millions of dollars in lost ticket revenue, as well as an uncertain commercial landscape in the coming years. In France, that has been compounded by the collapse of a television rights deal that would have provided the backbone of most teams’ budgets.

Firing a coach, meanwhile, is expensive. At the elite level, that can mean several million dollars to pay out the contracts of an incumbent and his staff, and the commitment of millions more to appoint a suite of replacements.

Fiorentina, for example, fired Giuseppe Iachini at the start of November, replacing him with Cesare Prandelli. The club is now paying the salaries of three coaches: Prandelli and Iachini as well as Vincenzo Montella, who was fired last year but is still officially under contract — paid, essentially, not to work. The club has the means and appetite to do that — the cost is borne by its owner, Rocco Commisso, the billionaire chairman of Mediacom — but most teams do not. “The mentality of team owners is just to get through this period,” said Stewart King, the global head of performance at Nolan Partners, an executive search and recruitment consultancy that works with a host of clubs across Europe to fill technical positions. “Teams that might want to be in the top 10 of their league are thinking that as long as they’re not bottom, what matters for now is that they survive and see what the world looks like on the other side.”

As well as the cost, though, there is a unique practical consideration this season. Allardyce, after his appointment at West Brom, admitted that it “might take longer than normal” for his methods to have an impact because training time is so limited in a compacted, congested calendar. With so little breathing space between games this year, most teams are restricted to recovery and recuperation; a new coach simply does not have time to introduce a new tactical approach.

But it is possible, too, that the pandemic — as it has in so many other spheres of life — has simply accelerated a change that was starting to occur naturally. “Most clubs now have a much more professional process when they hire a coach than they did 10 years ago,” said Omar Chaudhuri, the chief intelligence officer at the analytics consultancy 21st Club.

Whereas typically owners in need of a new manager would scan the market for the latest flavor of the month, or use a network of agents to identify available and willing candidates, now many clubs conduct a much more extensive form of due diligence.

Though Nolan Partners, for example, does much of its work identifying and recommending sporting directors, it is often brought in to source references and run the interview process for teams looking for a new manager. 21st Club is one of a number of firms that provide data and performance analysis not only on incumbents, but on their potential replacements. “Even when an owner or a chief executive has an idea of who they might want, they have to demonstrate a process,” King said. “It is much more sophisticated than it was.”

In Chaudhuri’s experience, that sophistication in hiring coaches has made owners less impulsive in firing them. “Clubs are much more invested in their appointments,” he said. “Executives increasingly look at the underlying numbers, and often are reassured by what they see, even if results aren’t great at the moment. They have put the work into finding the right guy, and they want it to succeed.”

King said at least a part of that shift is because of the increasing number of American investors — who tend, he said, to arrive with a “medium- to long-term mind-set,” and run their clubs along the general manager model common in American sports. “A sporting director lends a bit of air cover to the manager,” King said. “The days of the sporting director criticizing the manager because he wants the job are gone.”

The patience demonstrated in the straitened times of the pandemic, then, may be rooted as much in inclination as it is in necessity. But for all that soccer is starting to change — to grow more sophisticated, more thoughtful, less impulsive — some things stay the same.

Preziosi fired Maran on Monday, and replaced him with Davide Ballardini. The new man, at least, goes into the job with his eyes open: It is the fourth time Preziosi has hired him. There are no prizes for guessing how the other three turned out.